Ever since he burst onto the film animating scene in the early ‘60s, Hayao Miyazaki has been the manufacturer of dreams. Working initially as an in-between artist on a number of Japanese productions, he soon worked his way up the animating ranks, opening his much lauded Studio Ghibli in 2985. The studio was best known for its fantastical anime films, heralding story lines which took place in a kind of reality, situated just at the edge of the world that we think we understand. Of course, we all know that Miyazaki famously gave up the reigns of the studio last year after the release of the much celebrated The Wind Rises. Since then, Studio Ghibli has temporarily halted production, focusing on an internal re-shift before it begins producing dream-like films once more.

The question on everyone’s lips is, will things be the same after Miyazaki? Were the films that we loved and watched over and again so good because they came directly out of his mind or rather, because he had such a great team behind him? In this case, only time will tell but I do have a sneaking suspicion that, in order to work for Studio Ghibli in the first place, you must be magical in some way.

From the moment that Castle in the Sky was released in 1986 up until the most recent The Wind Rises, Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli have produced hit after fantastical hit, playing to an extraordinarily large audience. Where favourites lie, we we all be at odds with one another but surely, that is the beauty of Miyazaki? He has shown us endless worlds of magic and it seems that out there, there really is something for everybody.

Despite having released two other films beforehand, My Neighbour Totoro was arguably Miazaki’s biggest earliest hit, standing up as a cinematic classic to this day. The film tells the story of two young girls who have recently moved to the countryside with their father to be closer to their sick mother. Whilst exploring the area, the youngest girl stumbles across a gigantic nest, home to the huge and fuzzy Totoro. Totoro and his other spirit companions befriend the girls and begin to adventure with them. The film’s beauty lies in its innocence and positivity; the young girls are brought up to believe that you should honour and love the world around you and great things will happen. Tellingly, the film is set in post-war Japan, after the country had been ruined and broken down. My Neighbour Totoro speaks for the first time a message consistent in Miyazaki’s work: All is not lost.

Miyazaki wasn’t just about woodland spirits, of course, and in Kiki’s Delivery Service, he told the tale of a young witch in search of her powers. After leaving home for her year of magical discovery, Kiki settles in a new city by the sea with her cat Jiji. She soon opens a delivery service, bringing goods and messages between the city people with the aid of her trusty broom. The film plots the rift between adult independence and childhood experienced in teenhood. Although Kiki initially makes it on her own, she must continually overcome new challenges in order to develop fully. Whilst the film speaks clearly to children, its themes are just as relevant to adult viewers; although you may seem to have it sorted, there is always something new to learn and develop. By admitting her faults and recognising her strengths, Kiki is able to begin to thrive. And that’s a lesson that we could all learn.

In Princess Mononoke, however, things begin to grow up. Don’t let the name fool you; Princess Mononoke is not about castles and princes, she is one tough cookie. The film is set farther back in time than other Ghibli works, intensifying the fantastical elements and facets of ritual. Princess Mononoke is set in woodland and is primarily concerned with the interplay between ancient, natural spirits and the industrious, forward-thinking humans. The film inevitably ends in a battle-esque sequence and whilst other, earlier Ghibli works have resulted in the triumph of good over evil, Princess Mononoke is a little more cloudy. Whilst the burgeoning human population seem to spell downfall for the forest, they only work the land in order to survive. Although the evolution of society seems to spell bad things, it merely represents a state of change imperative in order for human culture to move forward. Princess Mononoke is made up of many shades of grey, presenting the real complications which punctuate real life and how, maybe, there is no clear right or wrong.

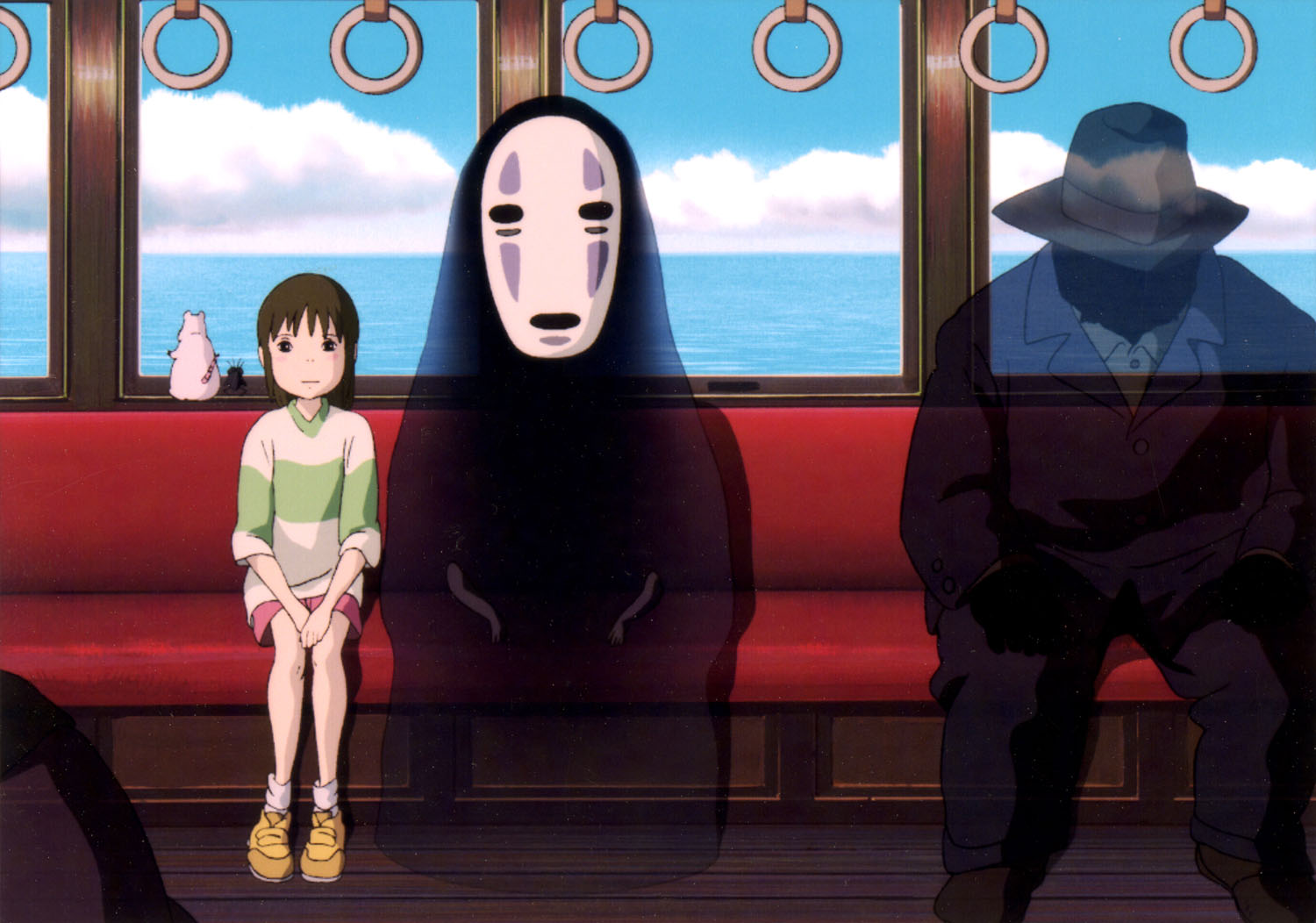

After gaining international recognition with Princess Mononoke, Studio Ghibli hit the mega big time with their 2001 release Spirited Away. Not only did the film become the largest grossing film in Japan ever up until that point, it won an Academy Award, the Berlin Film Festival Golden Bear and is now considered one of the greatest animated films of all time. That’s no mean feat for an animation about a girl whose parents turn into pigs. Spirited Away takes place almost exclusively in the spirit world, following a young girl who relentlessly attempts to free herself and her parents from the grips of the otherworld. In order to return to the human realm, the girl must work for the spirits, paying for her earthly freedom with her time and effort. Surprisingly, Spirited Away was produced without a script, a fact which, even more surprisingly, applies to all of Miyazaki’s works. Preferring instead to let the story develop organically, Miyazaki would not have a structured film plot in place until after work has begun on the film. Perhaps that is why the films work so well; in their loose structuring, Ghibli are enabled to constantly surprise themselves with their own ideas. The narrative comes as arbitrarily as real life seems to.

Studio Ghibli, whilst gone for a while, have certainly not been forgotten. When they return in the future, it is without doubt that the production will be indelibly altered. But that is not a bad thing. If we have learnt anything from Miyazaki it’s that change is inevitable. It’s how you react afterwards which is really important. For now, it’s over to Studio Ghibli.