The world is made up of countless things that we don’t even see. Our modern lives gravitate around the technological innovations that we have created for ourselves but, for the large part, we aren’t aware of their presence. We have become so used to our change world that we cannot perceive any difference between how things are now and how they were before. There are some, however, who haven’t forgotten the alterations we have made, who look deeper into the most minute of technologies and marvel at their creation. Podcast 99% Invisible is concerned with exactly that; the near-invisible, the tiny parts which band together to form the world in which we live. The show’s concept aims to uncover the overlooked and unseen elements of design and architecture which govern our world.

No matter too small or insignificant, the creators expand our concept of reality, proving to us just how much effort goes into each element which we take for granted. In one particularly memorable episode, the podcast looks at the science, or rather, the design of sound in the modern world. So many of the objects that we use are technological; whereas we used to rely on things which produced tangible effects, many of the objects we encounter function through the internet. They don’t work right before our eyes; they belong to a different sphere. However, in order to feel like something is working the way that a ‘normal’ object with, we need to hear it function. The problem, however, is that technological items are by nature silent. They do not crash and click and pop the way that, say, a hammer or a saw would. Of course, there are people behind the problem. Sound designers create new sounds to accompany the actions of silent objects. A normally silent mobile phone has a specific sound when it turns on. It makes a sound when it receives a message and a different one when it sends a message. We have become so accustomed to these noises that we fail to realise that they are not inherent to the device. We have become so attuned to them that, should we hear someone else’s phone make the same noise, we instinctively reach for our own.

Sound is a very strange thing. In our everyday lives, it connects us to the world around us, creating an imperceptible link between us and the things which we use. The sounds of the city remind us that it is still functioning, the normal sounds of our own reality assure us that everything is running normally. The absence of sound is often an indication that something is wrong, the precursor to something a lot worse. Sound in film in particular is essential to convince us that what we are seeing is real. Were we to witness a cinematic scene in which action and sound were adrift from one another, we would be alienated from the film world. Changes to sound would remind us that what we are seeing is not real.

There are a number of types of sound in film, each designed to affect our understanding of the film world in front of us and, hopefully, the way in which we perceive the film in hindsight. Animated films in particular rely on a fully formed sound landscape, utilising sounds as realistic as possible to overcome our distance from the film world. In this writer’s opinion, you can’t get better than Aardman when it comes to sound design and, inevitably, Wallace and Gromit is at the pinnacle of their empire. A Grand Day out sees the duo journeying to the moon after their cheese supplies fall dangerously low. Throughout the short film, the sound is realer than real; the dampness of the wet paint on metal, the soft muffle of footsteps on cheese, everything sounds as if it were a high definition version of real life. Every action (no matter how unreal) is connected to our reality through the crispness of the sound. Each action is played out with more intensity and as a result, we recognise the world of Wallace and Gromit as akin to our own.

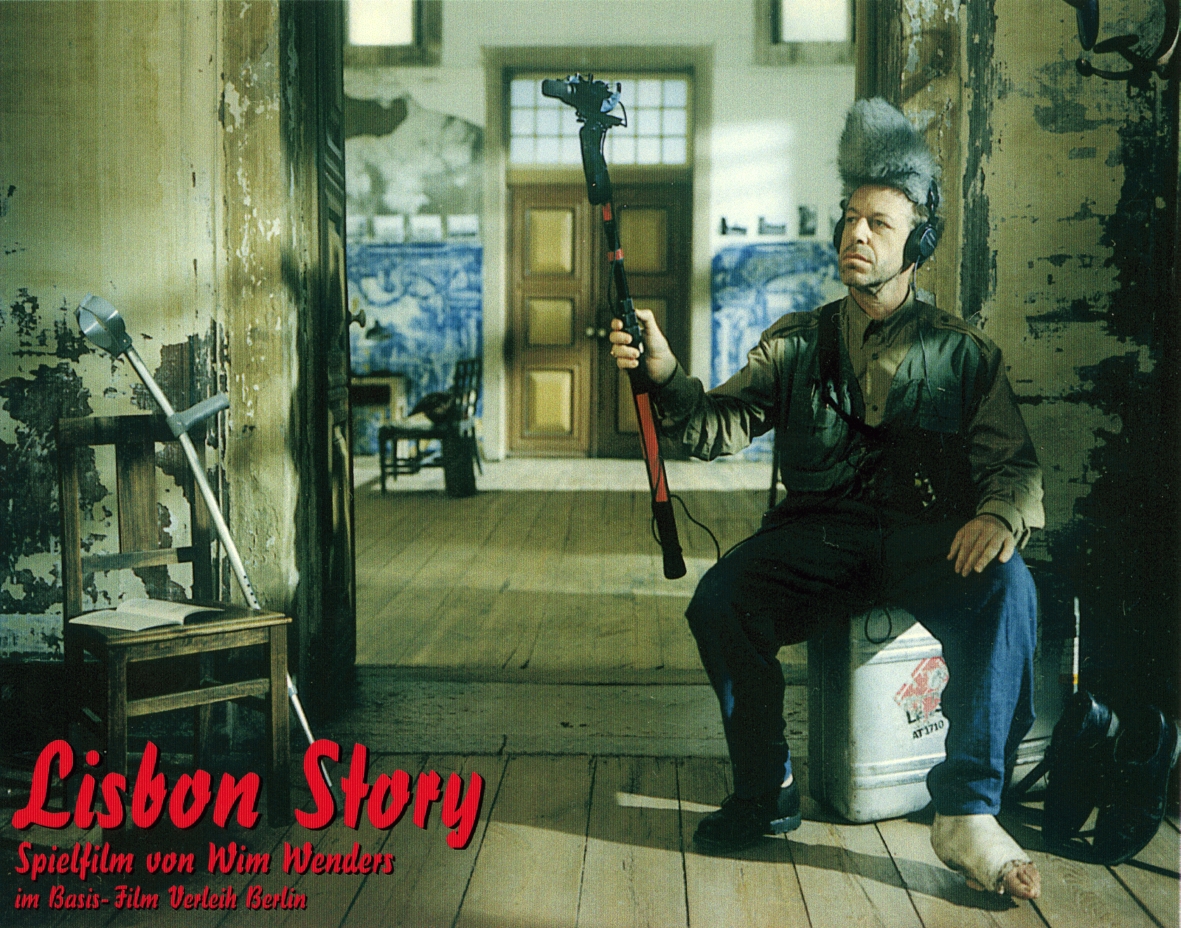

Films set in reality, however, don’t always have to go to the same lengths as those created in animation. Wim Wenders’ Lisbon Story is a film about film, following a sound recorder as he travels Lisbon to capture sounds for his friend’s new movie. Whilst there is little different about the way in which sound is captured in the real film, Wenders’ representation of the sound recorder replicating real sounds makes the viewer hyper aware of sound in general. Using foreign objects to replicate normal actions such as eggs frying and horses galloping, the sound recorder abstracts the notion of sound in reality. By dissociating the real sound from the place in which we believe it comes, the film highlights the duplicitous nature of sound, suggesting that, in film at least, we should not always trust what we hear.

Of course, sometimes sound can be used for completely different means, to open our eyes to a world we never even dreamed possible. Under the Skin centres around an alien entity as she drives around Glasgow, preying on the local male population. In a particularly gruesome scene, we are shown what the alien does to her victims, plunging them in a tar-like pool of black liquid. Beneath the surface, her victims float, their lives sucked out of them ever so gradually. The sounds beneath the surface are completely otherworldly, reminiscent of something we may know already. Bodies ripple through the liquid and joints crackle and pop. Everything is visceral, the sound turned up to the max to remind us that, as humans, we are completely out of our depth.

Sound is used as a way to place us more firmly in the real world but when we manipulate it, we create a divide between what is real and what is not. With the manipulation of new objects, given sound to appear more real, we already adjust reality. The world in which we live is hyperreal, a high definition version of how we lived before. Whilst sound in cinema may be more explicitly artificial, it is artificial in a knowing way, obviously representing a fake world. But, with the turn towards technology, could we say that the fake sounds on film are actually more real than those which we have created for ourselves?