Some things in our lives are so familiar and so well loved that we no longer notice them. They have existed so long in our minds that they seem somehow ‘part of the furniture’ but were they to suddenly disappear, we would be rocked from the very core, shaken to the ground and left in mourning. In film, there are plenty of figures like this, the people who seem to have existed in cinema since time began and without whom we couldn’t possibly envisage our viewing habits. Inevitably, though, we begin to take these people for granted, to assume that they will always be around and they somehow know how valued they are, without anyone ever having to tell them. Such is the case with Martin Scorsese.

For modern audiences, Scorsese is to cinema what bread is to butter; the two are irrevocably interconnected and to have one without the other would be entirely alien, leaving a strange taste in the mouth. It seems that the majority of the cinema-viewing world thinks nothing but good thoughts towards Scorsese and yet, for a long time, he went unnoticed in major ways. Although it is universally understood that he is one of the great American directors, he has only ever received one Oscar award, despite numerous nominations over the years. Whilst Scorsese’s win for The Departed was duly deserved, it seemed more fitting that he win the recognition for one of his other films. Although The Departed is not a bad film by any means, Scorsese’s win seemed more of a gratuitous victory, granted due to the snubs that he had experienced in other years.

Of course, award recognition does not a brilliant director make – Scorsese is living proof of this. And yet, the way in which official cinematic bodies have behaved towards the director over the years only continues the trend of our assuming that Scorsese knows just how great he is. And he really is. Scorsese has been responsible for some of the most memorable and oft-quoted moments in movie history. From the beginning, his cinematic approach has been so consistent and so his own that it is rarely difficult to spot one of his films.

From his early cinematic work, Scorsese showed such cinematic prowess and vision that it was impossible to ignore the mark he made on cinema to come. Mean Streets was the inception of the Scorsese gangster film, showing us a world known to cinema but packaged in a way altogether unique. The film is set in Scorsese’s native Little Italy, revealing a slice of the area’s underbelly, rife with gangsters and gang tensions. Rather than glamorising the violence, however, the film is focused on the notion of sin and worries about sin which circulated the society depicted in the film. Mean Streets was a thoughtful gangster movie; in a series of scenes, Scorsese developed his now famous slow motion camera, following his characters as if they were saintly figures, floating through the filmscape. The film also saw the start of Scorsese’s cinematic obsession with music, a trend which continues in his films today. Most famously, the film’s inclusion of Be My Baby by The Ronettes was due to Scorsese’s obsession with the music on set; he used to tap the song’s opening drum beat on his chair before takes. Mean Streets was the start of Scorsese’s reign on cinema and the moment in which we all sat up and listened to him for the first time.

Taxi Driver ups the ante somewhat and has become a classic of cinematic history. Not only does the film include Robert De Niro’s famous performance as the unsettling Travis Bickle but also, it contains some of the most interesting cinematic moments in all of Scorsese’s career. From the broken long take of Bickle walking the New York street to the “You talkin’ to me?” mirror sequence to the referencing of countless other films, Taxi Driver is an encyclopaedic film, as rich in cinematic technique as it is in narrative plot. Topped off with Ennio Morricone’s now iconic score, Taxi Driver seems to be a pinnacle in Scorsese’s career. Amazingly, however, the director just kept on getting better and better.

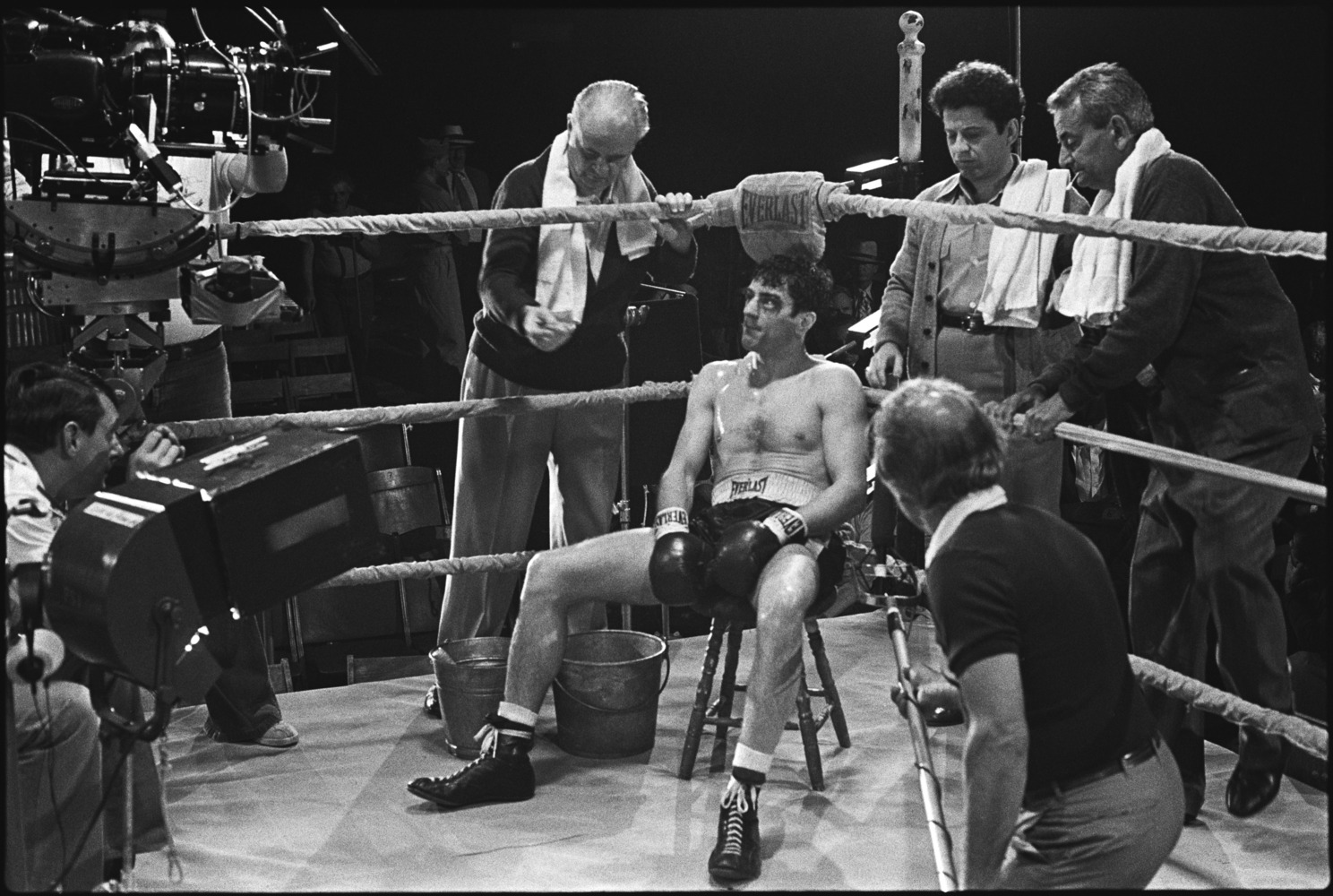

With the addition of Raging Bull, we have completed the early Scorsese triptych, the three early films which cemented his place in cinema’s hall of fame and critical appraisal. Starring Robert De Niro once again at the helm, the film follows the life and career of middleweight boxer as he makes his way up the ranks to boxing glory.Raging Bull has many similar traits of the other films listed and follows a trajectory similar to many Scorsese films. Whilst the narrative arc differs, Scorsese is concerned with the lives of the ‘underdog’ as they make their way through the ranks. Similarly, the film is more concerned with subtle changes in the relationships of the characters than it is about the world of boxing at large. In all three films and indeed, in his filmography, Scorsese makes the world on screen his own, filling it with characters who are both believable and recognisable.

Scorsese cemented his name as a top director with these three early films and his career since has been consistently interesting. Although he is normally associated with the gangster film, he has proved time and again that he is well versed in all types of cinema. In After Hours, he ventures into the twisted world of black comedy, in Bringing Out the Dead, he proves that, under his direction, any actor can be worthy. Recently, his foray into children’s cinema has added yet another dimension to his repertoire. Whilst Hugo is first and foremost a film for children, it is also about discovering (or rediscovering) the wonder of cinema, looking at the seventh art through fresh eyes. We believe that a stalwart cinematic presence such as Scorsese is set in stone, pushing the same ideas that they always have done. In his work, however, Scorsese shows us time and again just how fluid his vision is and why we should not forget about him as a very relevant figure in modern cinema today.