Although many of us don’t like to admit it, sometimes, there is nothing funnier than seeing someone fall over. Especially someone that you know well. Torn between helping them and laughing, our faces twitch between concern and hilarity, guilt and amusement. In moments such as these, we are all children and there’s nothing more satisfying than letting yourself go, opening your mouth and letting out a big belly laugh.

Slapstick is something incredibly difficult to pull off. Too much of it and you’ll have your audience bored to tears. Too little of it and you will suffer a similar fate. Sitting somewhere in the middle, the slapstick comedian needs to portray the ridiculous without coming off as being ridiculous themselves. They need to not be in on the joke and yet approach it with a wry smile. In short, they need to achieve the impossible and perhaps this is why the word itself is met with such distaste and irritation amongst the world of cinema goers.

In 1950s France, however, change was in the air. Attributed for so long as being the birthplace itself of cinema, France took its title very seriously indeed. Putting forward cinematic movements such as Impressionism and La Nouvelle Vague, France seemed incapable of making a joke. The cinema was beautiful but, with the rise and rise of Hollywood and the Golden Age blooming onto the scene, the French needed something new to rival the musicals from across the pond.

Jacques Tati was never meant for the silver screen. Looming above his contemporaries, dressed in shortened trousers and a paunchy hat, his very demeanour seemed at odds with the glamour and dramatics of the cinema screen. He moved like an overgrown deer, he mumbled into his chin when he spoke. He dropped things and forgot things, he poked and pulled and prodded and did everything that he wasn’t meant to do. And yet, somehow, he triumphed.

From the inception of his Monsieur Hulot character, Tati made a mark in slapstick cinema which has yet to be filled. Not only were his films incredibly funny and original but also, they were entirely sympathetic and heart-breaking; Hulot was a character who got everything wrong and caused mayhem in his wake and yet, all he wanted was to connect with the people around him. The lone, tumbling figure was essentially nomadic and alone. And that is a feeling to which all people can relate.

In M. Hulot’s Holiday, we followed a handerkerchief-ed Tati as he enjoys a week by the seaside. Causing havoc wherever he goes, it would be easy to assume that the character of Hulot soon becomes an irritation. Yet, in his unassuming nature and relentless journeying onward, Hulot becomes a sort of hero for the everyman. Disconnected from those around him and yet, eventually, forming lasting relationships with all whom he meets, Hulot is impossible to despise because he is so unaware of himself.

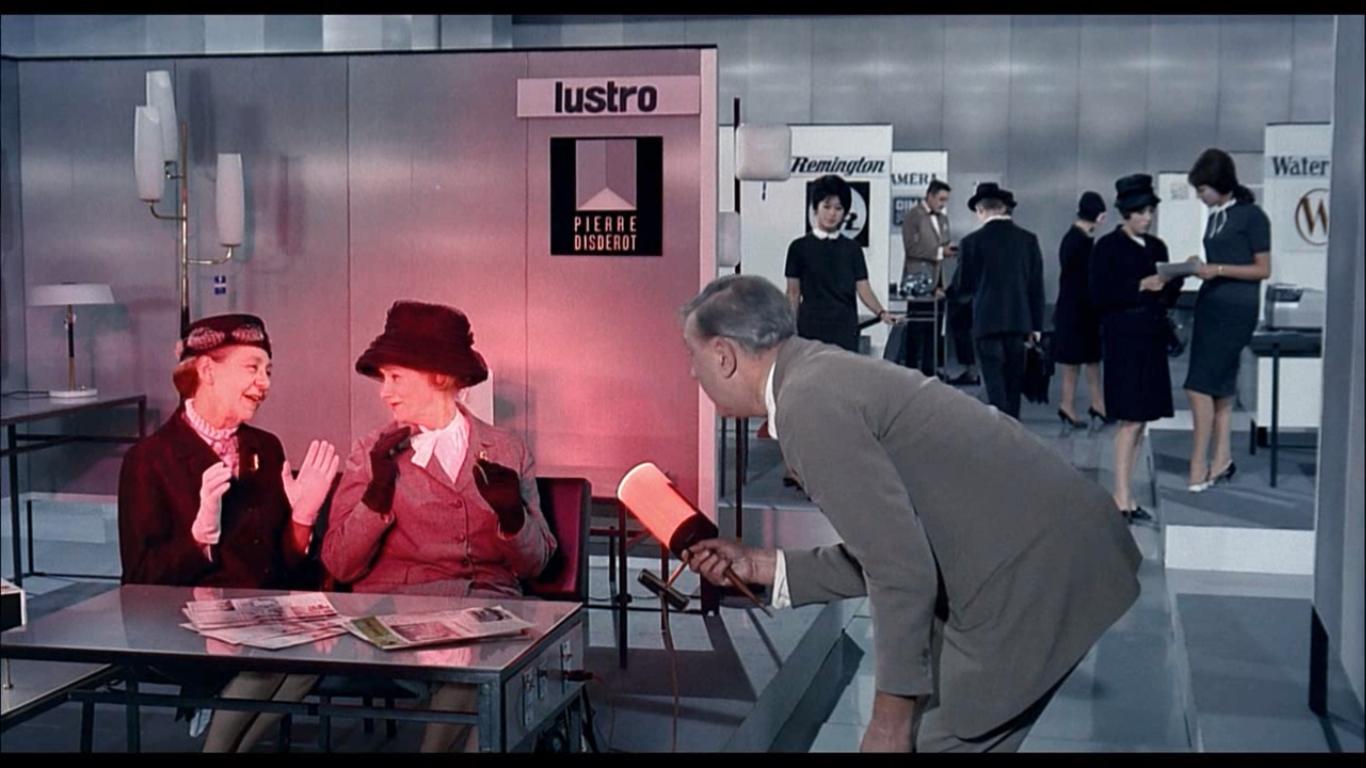

Playtime sees Tati at his peak. A looping, looming bird’s eye view of a falsified Paris, the film sees Tati’s character once more in the midst of inescapable destruction. From the opening moments and throughout the film, Tati leaves his mark in indescribable ways. The use of sound throughout the film is largely responsible for its comedic tone; giving inanimate objects voices of their own and imbuing all movement with isolated jazz riffs, the sound makes Tati’s world extrasensory, a place which we can feel forming around us as we watch it. Wreaking havoc on the streets of the would-be Paris, Tati was forced to build the city in miniature within a studio. Everything that appears on screen has an uncanny resemblance to the real place and yet, is so obviously constructed from false material. The world in which Hulot walks is fake and he is the king. Filmed from obtuse angles and a wide range, his looming figure seems distorted from afar, never quite fitting into the spaces which he inhabits. Tati’s camera is never obtrusive; regarding much of the action from a distance, we feel as Hulot must too, isolated from those around us, never permitted to join in with the fun.

Except that, this time, he is. In the scene’s longest and perhaps most impressive sequence, Hulot visits a new restaurant. From its opening to its eventual and inevitable demise, the restaurant marks Hulot’s eventual rise to success and his slow journey towards interacting with the world around him. In Playtime, Hulot is in his element; in the city that never really existed, the slapstick loner reigns.

Tati’s characterisation worked so well on screen because he never tried to make his audience laugh. And, indeed, much of his comedy came from the unassuming pose which Hulot took, or the nonchalant way in which he adjusted his hat. He made his audience laugh so that they might not cry.

And yet, his character was undeniably tragic. Behind the laughter and the buffoonery came a sadness and a willingness to do anything to be loved. In Sylvain Chomet’s devastating The Illusionist, Tati’s character enjoys fruition. Transposed to an illustrated world, Hulot is transformed into a struggling magician, nearing the end of his professional days. Subject to catastrophe after catastrophe, he bears all of the fruit of Hulot’s slapstick nature. Yet, the film is deeply affecting. In a particularly moving scene, the illustrated character runs into a cinema and is faced with the real Tati, running about on the screen. The magician stops, bewilderedly looking. For the first time, he is faced with the real version of himself, he is made aware of the fact that he exists as he is. For the first time, Tati sees that he has a place in the world and that, perhaps, was the thing for which he searched for so long.