We are living in a machine age. According to modern science and technological innovations, we are heading for an age unseen by any era before ours. The waters are unknown and muddy and whilst we are very much in the driving seat at the moment, there’s no telling where the future will take us. All over the world, technology is creeping ever closer to artificial intelligence, to the creation of a man-made consciousness. Whilst, in real terms, we may be some way off, we are certainly in the throes of making tentative baby steps forward.

According to Stephen Hawking, we should be afraid, very afraid, of what our steps forward could cost us. Were we to be able to create a self-improving computer system or a robot with real consciousness, it could spell the end of humanity as we know it. In recent cinema, technology is very a la mode and in the last few months in particular, we have been lead further and further down the technological rabbit hole, as directors ‘prepare’ us for what could happen in the future.

Overwhelmingly, however, artificial intelligence is rarely portrayed as a bad thing; it is normally our misperception and lack of understanding of it which creates fear amongst us. As we creep ever closer to the future, cinema has overwhelmingly changed its perception of artificial intelligence. Isn’t it time, then, that we do the same?

In the 1960s, we had our first taste of A.I. and man, was it terrifying. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey contained one of the most sinister robot figures in all of cinema; it’s hardly surprising that we’re a little edgy around man made beings. HAL 9000 (affectionately known as simply ‘Hal’) is present on the spaceship in order to make things easier for its human inhabitants. It is the omnipresent force of the ship, managing its functions. Soon, however, Hal’s consciousness starts to get the better of him. After having mistakenly detected a fault in the ship, the astronauts decide to turn off Hal, rendering him void. In order to avoid this and to ensure the survival of its kind, Hal takes it upon itself to kill both astronauts. An eye for an LED, and all that. The most unsettling thing about Hal is his consistent placidity; even when he is attempting murder, he remains calm and cold. Unlike other models, however, it is easier to distance yourself from Hal. The robot is presented in its bare, metallic state and as a result, it is easy to call out its belief in its own sentience.

More recent cinema makes things a little more tricky however, calling upon real people to play the part of robots. In Steven Spielberg’s overlooked film A.I. Artificial Intelligence, the boy of the moment, Hayley Joel Osment, played a young robot, purchased by a family to act as a companion to their son. Unlike other robots in the society, Osment’s kind was the first to be programmed to love and as a result, it is very easy to mistake the robot for something more human. Indeed, the robot is predominantly the most human part of the film, acting with more sensitivity and empathy than his human counterparts. The film is incredibly distressing and by the end, you may wish that humans become eradicated entirely. In A.I., we are shown how the creation can be better than the inventor.

Like all things technological, Charlie Brooker has also tried his hand at the artificial intelligence game and in his second series of Black Mirror, dedicated an entire episode to it. In Be Right Back, a bereft woman buys a computer system which aims to bring her dead boyfriend back to life by getting data from his online footprint. What starts out as a series of messages on a computer soon evolves into a voice and eventually, a body, mirroring her boyfriend exactly, copying his personality through coding. Of course, things start to become a little strange and living with a simulacrum proves to be too much for the young woman. The episode is incredibly chilling, making the simulation more real than reality. The computer system can perfect its model, adapting to changes and learning new information through its relationships. Although there seems to be little difference between the human and the android, it seems to be the fact of knowing which destroys the relationship. Knowing that the man is not ‘real’ prevents us from building a true relationship with it. As humans, we feel that our existence is more valid, more lasting.

Spike Jonze’s Her also looks at the relationship between a human and a computer programme. Whilst other works have focused on the human’s rejection of the machine in society, Her flips the equation somewhat, showing how the increased consciousness of the robot prevents it from wanting to enter society. The more that Scarlett Johannsson’s Samantha learns about the real world, the more that she realises she is adrift from it. Whilst the computer programme is a creation of the human world, it eventually becomes too big for it, essentially unable to function. The robot in this case is perhaps more sentient that the human; it questions its presence in the world with more urgency than human beings ever have done and in doing so, comes closer to decoding the world.

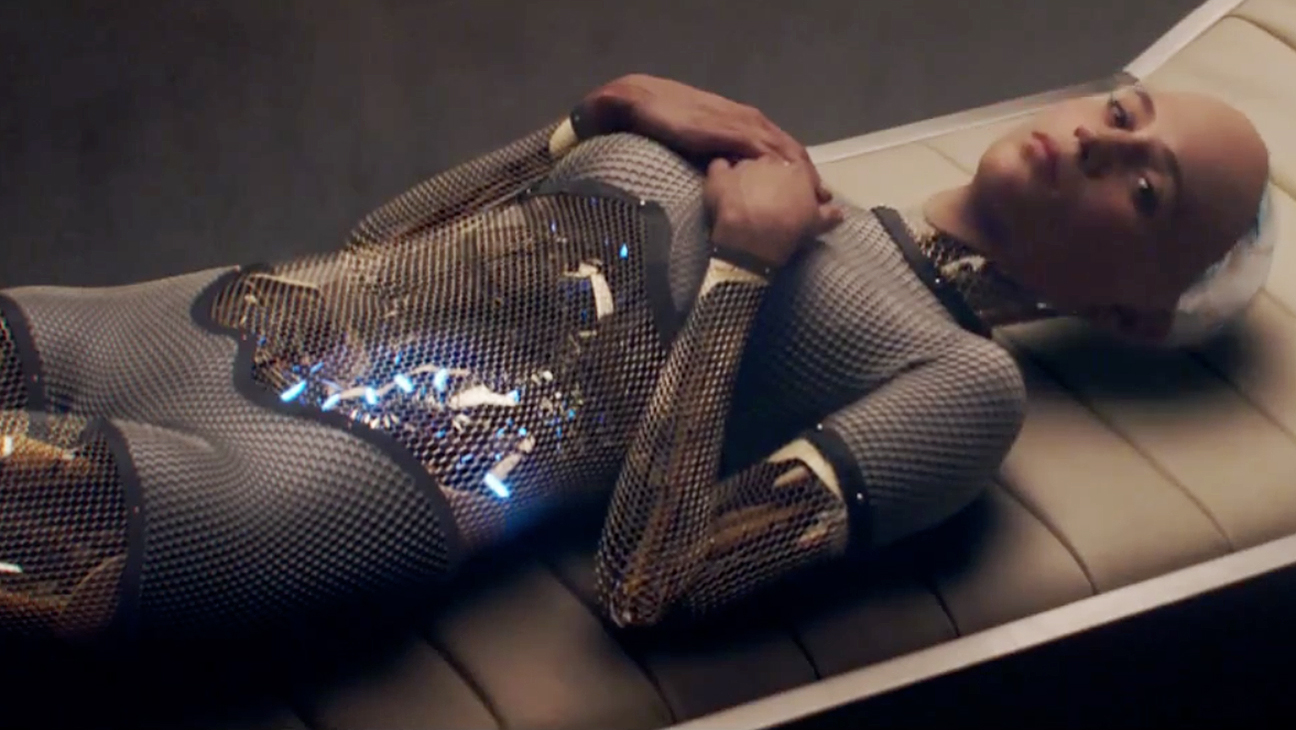

Ex Machina is the latest in a long line to look at artificial intelligence’s place in future societies. Like other films, Ex Machina questions whether or not it is possible for a robot to have consciousness in the same way that a human being does. In posing such a question, however, many difficulties are put in place and soon, it becomes clear that it is not so easy to answer. We are sentient because we know, we feel, we experience the world around us. But how do we prove that we can do this? How can we prove that others around us are the same way? How is it possible, then, to prove that a man-made machine, coded from humanity, cannot experience the same level of sentience? The further that we move forward, the increasingly blurry the lines become and soon, when we break through to the next stage of humanity, it will be impossible to tell what is ‘real’ and what is not. Consciousness and sentience as we know them will be forever changed.