We’ve all been there, nestled in our cinema seats, awaiting the feature film, brimming with anticipation only to be let down in the briefest of moments. “Everything that you are about to watch happened over the course of 6 months. All the participants and the action shown ARE REAL” flashes on the screen and, as quickly as we have read it, we are instantly let down.

When we read disclaimers that claim the validity of the following footage, internal alarm bells immediately ring. It is as if we have been hard wired to smell a rat. Films which feel the need to shove their honest-joe approach to us are impossible to consume without a massive dollop of strong, white salt. And indeed, the films themselves play into this knowledge, half-heartedly perpetuating their myth. When a film claims to show us only what is real, we only need believe it for the running time. After that point, we can move on, store it in the banks of our memories and stop thinking about it.

There are some, though, that won’t allow us to do this. Caught up in their own story, they continue to proclaim their veracity, never for a moment letting down their guard. Films such as these live for a much longer time in the social imagination, not because they are necessarily better than other movies at the time but rather, because we feel the inherent need to prove their veritibility wrong.

We obsess over movies such as these, watching them and rewatching to pick apart any holes they may contain. We research them, we write about them. We create the myth around the movies so they don’t have to.

Ever since cinema began, filmmakers have been trying to fool their audiences. From the Lumiere brothers’ The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat, films have shown their audiences something unreal, cloaked in a cloud of realism. As very early documentaries filmed reality, they got their audiences to believe that what they were watching on film was quite literally happening in front of their eyes.

Ever since cinema began, filmmakers have been trying to fool their audiences. From the Lumiere brothers’ The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat, films have shown their audiences something unreal, cloaked in a cloud of realism. As very early documentaries filmed reality, they got their audiences to believe that what they were watching on film was quite literally happening in front of their eyes.

During the first screenings of the Lumiere brothers’ documentary short, audience members ducked out of the way, diving to dodge the speeding train which seemed to be making its way towards them on the screen. Of course, since then, cinema has become a little more complicated. Filmmakers have become a lot more savvy, able to manipulate what the audience sees or think they see through editing, sound design and lighting.

Orson Welles’ F for Fake was perhaps the first film to deliberately fool its audience, claiming to be investigating the artist forger Elmyr de Hory. Fooling art critics over the world, de Hory replicated and created paintings by the masters of art, seamlessly mocking their style of painting. What the audience did not expect, however, is that Welles would pull the wool over their eyes as well.

Focusing on the beautiful granddaughter of an unknown forger, Welles told the story of how he created a new collection of Picasso paintings, simultaneously creating waves in the art world and enraging the painter himself. At the end, however, Welles made a happy confession. Whilst he promised to tell the audience the truth for one hour, for the last 17 minutes of the film, he had been lying his head off. Haw-haw indeed.

Whilst Welles admitted to his forgery with much pleasure, there have been countless others who have either reluctantly come clean or, for some, not at all. The found-footage documentary gained momentum in The Blair Witch Project, the original shaky-cam, heavy breathing ‘mockumentary’. Unlike films of the same nature today, the makers of the film went so far in their attempt to fool the audience that they even lied to the actors behind the lens.

Creating a huge canvassing campaign months before the film was even released, the job seemed fool-proof. However, inevitably, the secret couldn’t be kept shut. Joaquin Phoenix’s I’m Still Here followed much in the same vein, going so far that for months, the actor humiliated himself in front of national audiences and celebrated musicians following his bid to become an international rap star.

Creating a huge canvassing campaign months before the film was even released, the job seemed fool-proof. However, inevitably, the secret couldn’t be kept shut. Joaquin Phoenix’s I’m Still Here followed much in the same vein, going so far that for months, the actor humiliated himself in front of national audiences and celebrated musicians following his bid to become an international rap star.

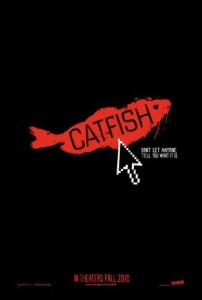

Some, however, have gone a little further. The huge success of the film Catfish has spread so far that the word has had a new definition added in the dictionary. Following the plight of one young man who really should have known better, the film looks at the world of internet dating and the ways in which people deceive the ones they love. Despite the suspiciously neat narrative arc of the film, all three members of the filming crew claim to this day that what was shown was exactly what happened. Their protestations of innocence have gone so far, in fact, that the main protagonist of the film has gone on to host his own TV show.

If Catfish has taught us anything, it’s that we cannot trust anything that we are shown on the television. But then, we knew that already, didn’t we? Living in a world in which the lives of apparent strangers are just a mouse-click away and breaking news reaches us through social media before all other portals, it seems that everything that we know to be true has come to us via virtual reality. We know that ‘reality’ films are 100% constructed, we only allow ourselves to believe as much as we like to. What we should question, then, is not the films which claim their reality but rather, the information we obtain online which feels it does not have to.

When the internet has somehow become the voice of reason in the world around us, we must question the reality of our entire existence.