Watching any film by Austrian director Michael Haneke is akin to having your teeth pulled. Whilst you know the final result will be worth it and it’s bettering you in some way or another, the process can be, at times, entirely unpleasant and painful. Haneke is the director in all of the film world most frequently parodied and made a mockery of, all with the most loving of intentions, of course. His parody Twitter account currently stands at 33 thousand followers strong and whilst it was revealed a few years ago who was behind the tweeting, followers continued to flock in their thousands. Based around the director’s relationship with his cat and lack of ability to spell properly, the account gently pokes fun at Haneke’s predominantly serious cinematic tone and his apparent inability to laugh at himself. Whilst it was clearly faked from the off, there is a certain kind of pleasure which comes from believing that the director himself is behind the feline ramblings.

With Cannes 2015 just around the corner and a new Haneke offering potentially on the cards, what better time to look back at the work of the gloomy director? Although no-one knows whether the director has even begun work on his upcoming film Flashmob, speculation remains rife and many are convinced, nonetheless, that it will have a starring role in the French Film Festival. Either way, Haneke’s ghost will be present at the festival; having won the much sought after Palme d’Or twice already, his influence can be felt in so many new directors’ work.

From the off, Haneke has been winning recognition and festival awards for his work; despite the predominantly hard to swallow content, critics and film fans can’t seem to get enough. His second film, Benny’s Video, has gone down as a classic in his filmography, showing the director’s obsession with human nature and the personality-horror genre. The eponymous character is a young boy obsessed with the video of a pig being slaughtered, which he watches on repeat in his dark room. When he invites a girl over to watch the film with him, things turn entirely dark and soon, Benny is living inside a nightmare reality, brought about by obsession with real violence. What is most terrifying about the film, however, is not the actions enacted by Benny but rather, his and his parents’ reactions to their aftermath. Haneke presents the family unit as completely apathetic to the violence in which they live and how, instead of taking responsibility, they shirk all blame and ownership. In Haneke’s eyes, humans are led by instinct entirely and see no moral responsibility in their actions.

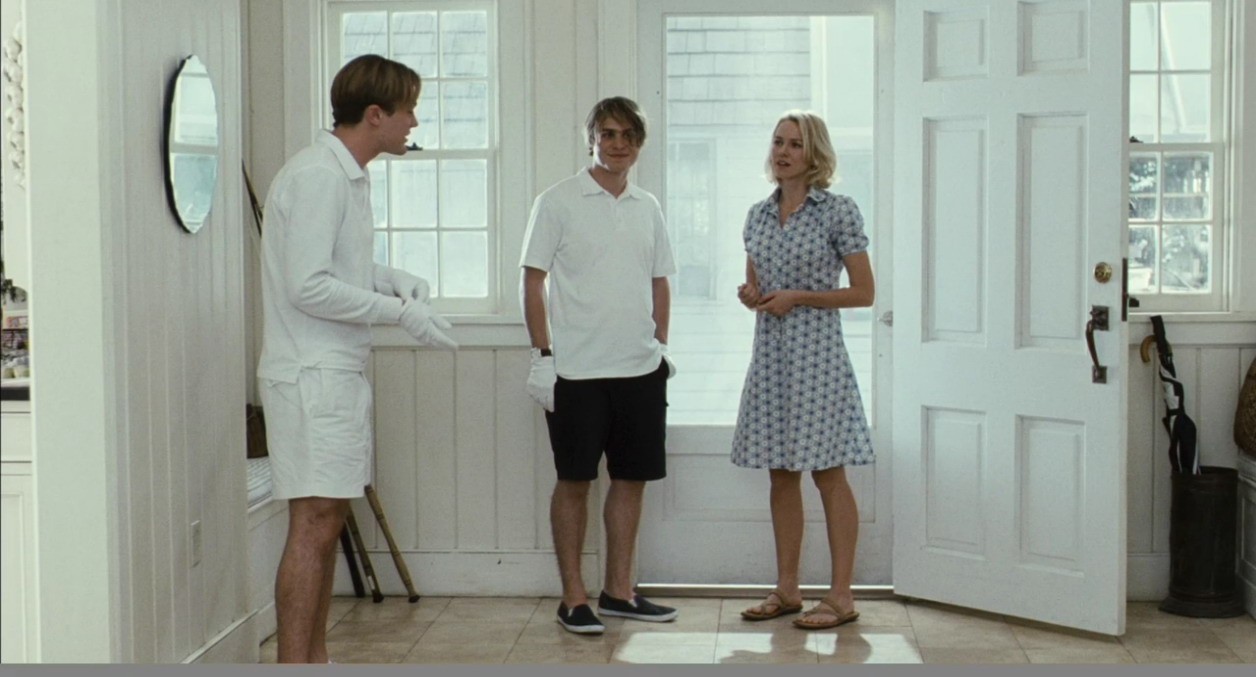

Funny Games is one of Haneke’s most watched films. Made originally in Austrian and later in American English, the film takes place over a course of a day or so in a country house setting. Two young men take it upon themselves to enter the home of a wealthy family, hold them hostage and subject them to brutal, prolonged torture, without reason. The film is incredibly difficult to swallow and whilst it is clearly a comment on video and audience culture, can come on a little strong at times. The film is famously self-referential; in one sequence, the intruders pick up a remote and rewind the film in which they star in order to change the course of events. The actors lambaste the audience for their complicity in the events on screen, asking time and again why they continue to watch the film. Truthfully, there is no right answer to their questions. They enact horror and we continue to watch, unblinking.

Caché, meanwhile, represents a horror which goes largely unseen, hidden beneath the bourgeois lifestyle of the central characters. When Georges, an established talk show host, begins receiving videos of him and his family filmed in their home, he becomes obsessed with hunting down the perpetrator, taking matters into his own hands when police refuse to help. Over time, the nature of the video becomes more personal and starts to lead Georges back to a part of his past which he had suppressed. Its conclusion makes for an incredibly uncomfortable watch and whilst some of the plot is made obvious, there is a still a lingering sense of menace at the end. In the film, Haneke seems obsessed with the passivity of the middle class family at the centre and how Georges’ refusal to admit responsibility for events in his past continue to haunt him throughout his seemingly comfortable life.

Continuing the theme of hard-to-swallow-cinema, Haneke’s 2009 Palme d’Or winning The White Ribbon makes just as hard a watch as his other works. Set in a German village in the early 20th century, the film centres around an accident which takes place towards the start of the narrative. When the village doctor falls off his horse and becomes seriously injured, the village’s facade of order starts to slowly crumble. Soon, other tricks are being played on different members of the village and what starts out as a small-time activity soon grows into something much more insidious. The film is slow and brooding, which only makes the action on screen harder to swallow. The relationship between a parent and their children is brought under intense scrutiny; what was once a sacred bond becomes, in Haneke’s eyes, something much darker.

With 2012’s Amour, Haneke picked up his second Palme d’Or. Although the film is not violent or aggressive in the same way as his other works, it is nonetheless incredibly heartbreaking and painful to watch. Set within the same Parisian apartment, the film depicts the relationship between an elderly couple after they discover that one of them suffers from severe Alzheimer’s. The film plays the last weeks and days spent between the pair and whilst there are few dramatic moments, it is an incredibly intense and stressful film to watch. Haneke’s representation of love feels more real than anything else out there; it is in the moments of quiet that he really pinpoints what the couple feel for one another. Whilst dark and tragic, Amour finally shows a softer side to the director and how, through his films, he is able to see human nature more clearly than anyone else.