More than ever, it’s a time to be curious. Things that we thought were set in stone are being unearthed and looked at in a more scrutinising way. Universal truths and social givens are constantly being re-evaluated. As much as we are looking forward, we are consumed by things that have happened in our own pasts and it’s not beneath us to take it upon ourselves to conduct a little detection.

We are currently in the midst of a widespread sleuthing moment; on the streets, in the newspapers, amongst our friends it seems that there is one thing we cannot get out of our minds. Serial. Ever since its podcast debut some nine weeks or so ago, more and more of us have become consumed with the seemingly simple and yet frustratingly uncrackable murder case unearthed again by Sarah Koenig. Just in case you haven’t got the memo, the podcast looks at the 1999 murder of American teen Hae Min Lee, who was strangled and buried in rural Baltimore. Pretty soon, her ex boyfriend, Adnan Syed, was arrested and convicted of her murder, filling out the whole ‘thwarted ex takes revenge on their former flame’ cliche. The thing is, the evidence doesn’t quite match up. And everyone involved seems to have contradictory remembrances of the event.

We are currently in the midst of a widespread sleuthing moment; on the streets, in the newspapers, amongst our friends it seems that there is one thing we cannot get out of our minds. Serial. Ever since its podcast debut some nine weeks or so ago, more and more of us have become consumed with the seemingly simple and yet frustratingly uncrackable murder case unearthed again by Sarah Koenig. Just in case you haven’t got the memo, the podcast looks at the 1999 murder of American teen Hae Min Lee, who was strangled and buried in rural Baltimore. Pretty soon, her ex boyfriend, Adnan Syed, was arrested and convicted of her murder, filling out the whole ‘thwarted ex takes revenge on their former flame’ cliche. The thing is, the evidence doesn’t quite match up. And everyone involved seems to have contradictory remembrances of the event.

Each week, Koenig digs deeper and deeper into the case and yet, becomes further and further distanced from the truth. It seems as if time and memory are inherently against her as each individual struggles to remember the facts the further they move away from the event. Another problem is, it is nearly impossible to be subjective when conducting a murder investigation. Despite her lack of certainty, it’s pretty clear who Koenig’s favourites in the investigation are and subsequently, who the listeners’ will be.

More than ever, we have taken it upon ourselves to crack the seemingly uncrackable cases put before us in life. More than ever, we seem to have lost faith in the figures of authority put in place in order to solve life’s great mysteries. When it comes to sleuthing, it seems that all bets are off and there can no longer be nice guys versus bad guys. Everything becomes a tinged shade of grey and we can only trust ourselves.

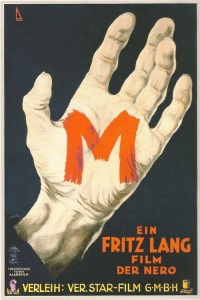

In cinema, this has been a trend that has existed for a long time. It seems that directors and writers are less inclined to trust the judgments of others and feel the need to create lone vigilante characters, usurping police and detectives to find their own version of the truth. As early as Fritz Lang’s masterpiece, M, we can see how social figures shift their behaviours to become plain clothes sleuthers. Whilst we are used to witnessing the individual battling the odds to find the truth, in M, an entire society bands together to find the child killer who is plaguing their streets. In moments such as these, a collective consciousness forms, eliminating subjectivity in order to pinpoint a threat in society. The crowd mentality is at its best in M; enraged and affected by the same cause, the crowd is efficient, somewhat objective and ultimately, successful.

Often, it is the camera who is the victor, cutting through the subjectivity of the human eye to define the truth. In The Thin Blue Line, Errol Morris restaged (to some extent) the murder case of a police officer, using similar techniques to the ones Koenig employs in her podcast. Working from actual testimonies, film reconstruction and just a little cinematic liberty, Morris presented the case from an alternative angle, which eventually resulted in the changing of a conviction. Despite its swerving into fiction here and there, The Thin Blue Line allowed Morris to solve the case precisely because it made the information more digestible. Contained within film, the case became cinematic and therefore, enabled us to comprehend its multiple elements at once.

We are able to be subjective and discover the truth, too, although with varying results. In The Bride Wore Black, a widow takes it upon herself to exact revenge on the men who were responsible for her husband’s death. Tracking down each one, she exacts a black widow-like revenge on them, finding some kind of solace in the pain which she causes. However, the end of the film reveals the truth about the case. Her husband was shot by accident by the men as they scrambled over a shotgun from a window. It is unclear in the film whether the woman is aware of the true circumstances of her husband’s murder. In any case, it is doubtful whether or not it would make much difference. To the woman, the entire case is personal and the way in which she goes about bringing justice is made equally person to each man involved.

Sometimes, however, it is the broken down detective figure who is able to find the truth. In Chinatown, Jack Nicholson’s Jack Gittes is hired to solve petty marital affairs and domestic issues. Finding himself involved in yet another case of the cheating husband, Gittes soons stumbles across something entirely more intriguing, implicating the husband in a case far more sinister. Despite his position in society, Gittes is clearly disingenuous in his role in the early part of the film, taking his ability to unearth domestic scandal as more of a joke than anything else. Soon, however, he mimics the true behaviour of a detective, becoming increasingly entangled in the web which he so desperately attempts to unravel. Such is the same with Koenig; the deeper she gets into discovering the truth, the more tightly she bonds herself to those around her, somehow implicating herself in the case. When we really care about a mystery case, we somehow make it about ourselves, too, losing all objectivity and clarity. When we finally discover the truth, it hits us right between the eyes.