What is real and what is not? It may seem far fetched but in the culture of today, it is hard to know what is part of reality and what is something that we have made up. Commercial culture and reality have become so intertwined that it is difficult to know when one ends and the other begins. The amount of time that we spend on portable technology means that they start to blend into our reality; it is perfectly normal for people to spill their secrets to strangers they have met online because they believe that they have built a genuine friendship.

And haven’t they? Contemporary culture has normalised these false exchanges of intimacy in such a way that we no longer feel we have to leave our bedrooms in order to have had a socially rich day. Whilst social media and portable technology is at the heart of the new displaced reality, it was television which initially pushed the idea. Showing us endless television shows in which scenes of apparent veracity were shown throughout, the people behind reality TV made us reconceptualise our idea of reality. Whilst many of the early shows were fly on the wall and a little off the cuff, the makers of the shows soon became savvy to their genre. Packaging a series as real meant that they could reach viewers in ways never before. Having ‘characters’ say certain things or use certain products influenced our behaviour in ways much more lasting than other television dramas. Placed in ‘reality’, we believed that the products they used and choices they made were intrinsic to their personality. We idolised them and so we adopted the same trends.

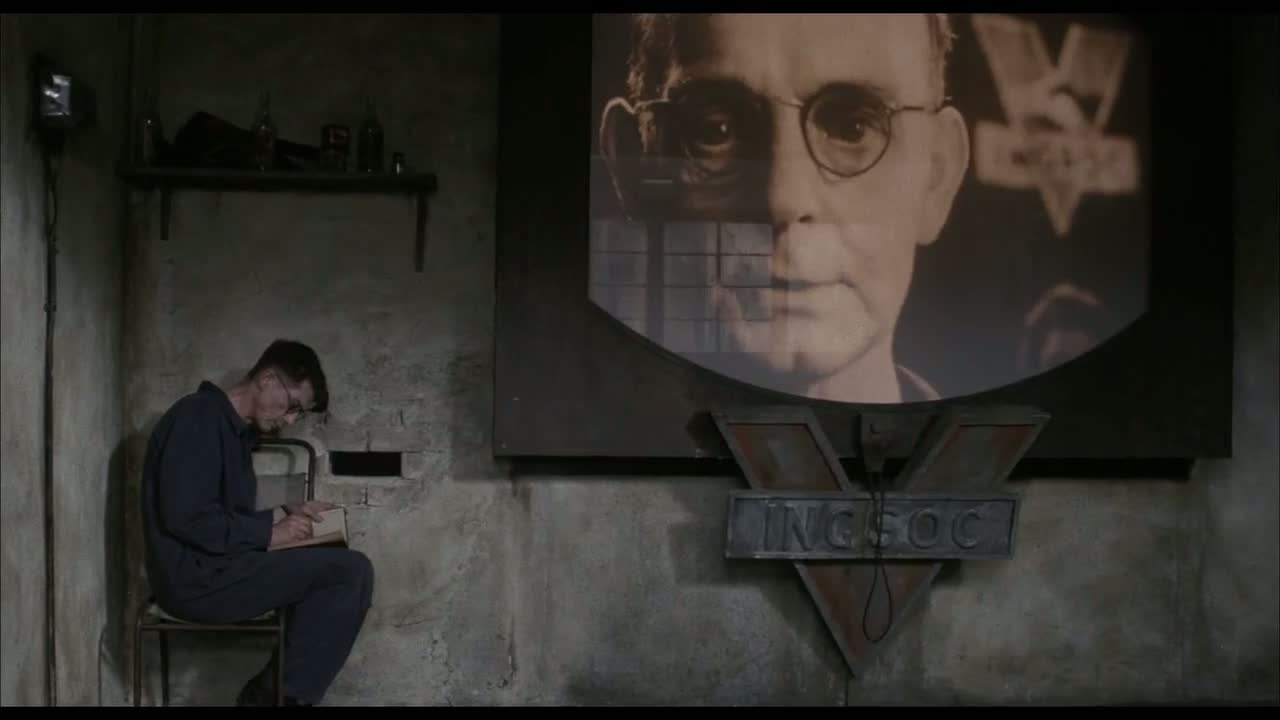

It all started with George Orwell. In 1984, one of his most heralded novels, he imagined a surveillance state in which all members of the population are looked over by an omnipresent figure, Big Brother. When individuals disobeyed the rules of the state, they were taken to Room 101 in which their deepest fears were realised. In 1984, Orwell anticipated the potential future with horror; our need to watch people around us resulted in a dictator state. Worse than that, the dictator had eyes and ears everywhere; the movements that people made were monitored and tracked at all times. It is ironic, then, that the television programme Big Brother chose to reference Orwell’s social imagining in its very concept. The sinister eyes of Big Brother became the gawping gaze of the general public who watched a group of mismatched members of the public argue with one another for twelve weeks. What was once a warning to the public became a place in which to zone out, mindlessly watching people doing nothing for 24 hours per day.

With Big Brother, our concept of reality shifted. We were told we watched people who were a part of reality and attached to our world but as soon as we placed them on camera, we changed entirely how they functioned. They formed a mini society, an off shoot of the culture in which we lived and, in way, we were their keepers. By watching them and investing time in them, we made their existence more meaningful than our own. We watched them doing nothing, just as we did nothing and in doing so, made their actions entirely false. We would reference things that happened in the Big Brother house as if they were a part of our reality, as if we knew the people to whom they happened.

Of course, since Big Brother, there have been endless remodels of the concept. Most popular, it seems, was the reality/drama series which showed us a slice of life from those of more privileged means. Whilst shows such as The Hills and Made in Chelsea proclaimed to grant us access to a world of which we could only dream, in fact, they showed us something entirely different. Fueled by drunken arguments and ludicrous plot twists, they told their audience that this is what they should aspire to. The lives of the very rich circulated around love affairs and infidelity and if we didn’t get a stake in it, ours were meaningless. If we didn’t invest our interest in the shows, then we were not connected to the people around us . In short, we were not a part of our own reality.

Without realising it, we have become cruel. In 2005, Space Cadets was released in the UK. Promising its participants a trip into space, it put them through rigorous testing and exercises. Of course, it was all a hoax. Its participants weren’t aware of this fact, however and when, mid-flight, their space shuttle began to experience ‘major malfunctions’, they feared for their lives. At least we were entertained. We watch television shows like The Kitchen and Gogglebox, whose premises centre around our observation of members of the public watching television. How meta have we become? Our sense of the world around us has become so skewed that, in order to enjoy ourselves, we watch people like us doing the same thing. We act up and make bold, meaningless statements in the hope of getting on reality TV and making our mark.

Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror holds up a mirror to our distorted perception of reality. People are tortured by vapid, unrelenting TV shows, by the search for hidden talent. They watch and participate in the same thing, year after year, only to forget about it in its immediate aftermath. Perhaps Orwell wasn’t so wrong after all. Our need to capture ‘real people’ on television has transformed our society into a surveillance state. We watch the people on television and scrutinise their movements as if they have a direct effect upon us. We herald those who we love and punish those we don’t more fiercely than we would in reality. They have become our reality. Everything else is just the blank space in between.