As a generation, have we become desensitized? The amount of violence and graphic imagery that we are shown on a daily basis would suggest that perhaps it just doesn’t affect us like it used to do. The news and media alone are responsible for a large majority of what we are shown and they are merely broadcasting what has actually already happened. People might say that we are living in a time of violent desensitization, in which we have become so used to distressing imagery that it simply no longer affects us.

They have got it all wrong. We mustn’t look at the effect or supposed lack thereof that such graphic scenes have had on us but rather, the reason why we have become so fascinated by them. If we take the distressing reality of the international news out of the picture, we can nonetheless mark an increasing trend towards blood and guts in television and film. For the past few years, we have turned to on screen violence as a way of escaping from something else or as a marker for something else. Instead of representing a turn to something much darker in our social mindset, violence on screen can sometimes be indicative of something else, closer to social unrest. The visceral nature of some films and TV series represent a rift in the way in which we think, not a universal bloodlust. A number of television shows and films mark different trends in the way in which horror and violence are depicted on screen, each one telling us something about the nature of the current moment.

We all know how I feel about Game of Thrones. Let’s not bring it all back again. However, even I will admit that there is something interesting to be said about the show’s depiction of violence and gore. The time in which the series is set is, by nature unforgiving and brutal. The slaughter of a pregnant lady is brushed away with a swipe of the hand. And yet, there is something somewhat positive which can be taken away from the programme.

The immediate shift to violence in the face of adversity brings together the members of each tribe much more closely than it would were they to use language as a weapon. Living in violent times brings people together in fully functioning collectives; people work together towards a common goal, they become a collective organism. In today’s society, perhaps this is something for which we long. Whilst we would never condone violence and terror in the name of social building, we use its representation in shows like Game of Thrones as a sort of parable. We live at odds from one another; brought together through artificial means, real human interaction has been all but eradicated. We want to feel one another again, build tribes of sorts.

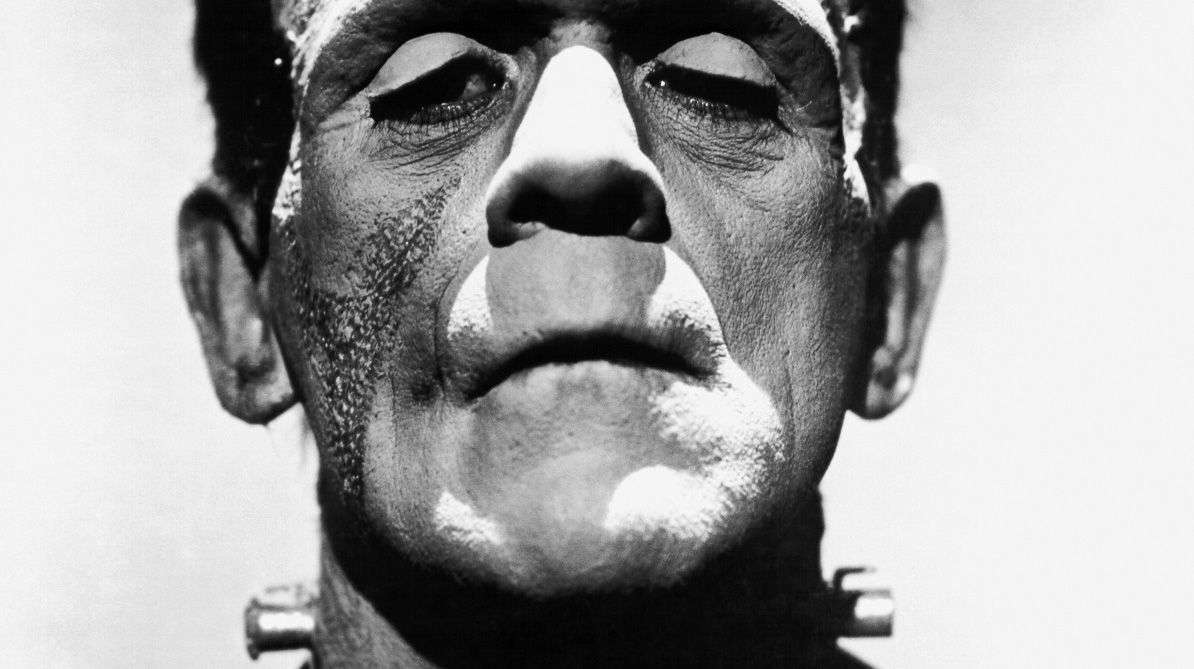

American Horror Story is the show of the moment. Taking us to places present only in the darkest of imaginations, the gore and body matter alone in the series are enough to turn even the strongest of stomachs. Horror is at the heart of the series and an episode which doesn’t feature its fair share of the undead visceral matter is not worth talking about. And yet, the programme is hugely entertaining as it acts as a form of escapism. In the Victorian ages, times were tough. Money and food were scarce, disease was rife and social unrest was at an all time high. Suddenly, stories about the supernatural were popping up all over the place. Frankenstein, Dracula, The Strange Case of Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde were just a few of the novels which gripped their readers. People everywhere turned to the dark side as a way to escape their own dreary realities and it seems that we are going through a similar period right now. For the last few years, films and programmes with darker content have flourished on our screens. In the midst of the financial crises, international pandemics and wars, we have turned once more to the supernatural to quench our need for escapism.

However, there is a fine line between escapism and gratuitous violence and whilst it is perfectly acceptable to enjoy the sillier dramatics of shows like American Horror Story, we must not forget that what we are dabbling in is very dark indeed. In 2010, Michael Winterbottom released a film adaptation of Jim Thompson’s novel The Killer Inside Me. The film depicted the story of a small town Sheriff who hides his sociopathic, violent tendencies behind a very thin veneer of normality. Played hauntingly by Casey Affleck, Sheriff Lou Ford’s life soon takes a downward spiral into the depths of darkness as he finds himself surrounded by the murder and violence which he so freely inflicted on the people around him. In perhaps the film’s most infamous scene, Winterbottom depicted in painful closeup Ford beating up his girfriend.

Unflinching, unblinking, the camera steadily captured the entire act, refusing to move its gaze. The scene is incredibly distressing and impossible to watch. By seemingly normalising Ford’s act of violence, Winterbottom holds up a mirror to other depictions of violence on screen. Natural to most thrillers and action films, the violence that we see in many films goes almost unnoticed by us. As it is integral to the plot, we brush it aside as inevitable. By doing this, Winterbottom seems to argue, we pacify the very horror of the act itself.

It is moments such as the one in The Killer Inside Me which make people think that we have become desensitized to violence. But really, our apparent flippancy is merely a coping method, one which we have to initiate in order to stay sane. For, if we were to react how we should to events in the world around us, we would turn completely mad.