Some characters stay with us for our whole lives, looked back on in fondness in moments of nostalgia, always picking us up when we feel down. Some characters do this for an entire historical generation, encapsulating such a specific moment in time that it seems as if they were entirely responsible for it. And perhaps they were. TV and cinema characters exist in the social consciousness as something greater than they are, representative of an entire moment in history, its politics, its social happenings and its population. It is as if, through these characters, we can look our history directly in the face and learn everything that it ever thought.

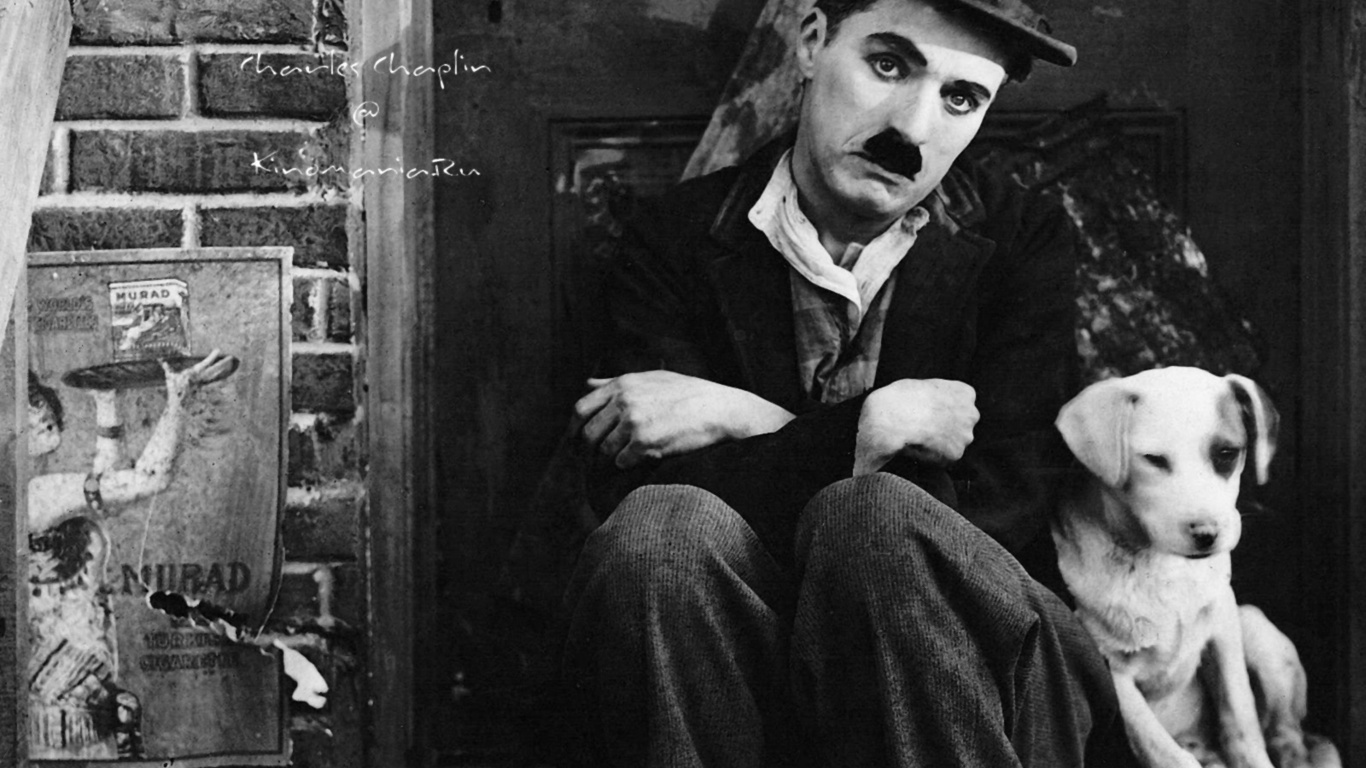

Some characters outlive their history and their maker, becoming something greater than anyone could ever anticipate. In the case of Charlie Chaplin, his Little Tramp figure is perhaps one of cinema’s most enduring icons. When we think of Charlie Chaplin, we see the figure of the tramp. The two have become so indelibly intertwined that it is hard to see where one begins and the other ends. For many, Chaplin was the tramp and seeing him out of costume is a very strange experience indeed. The birth of cinema seems to have come from the inception of the Little Tramp and, whilst we know differently, there’s no denying that the way in which we perceive cinema nowadays is due, in part, to Chaplin’s legacy.

The Little Tramp was created on something of a whim, concocted out of dregs of other costumes which Chaplin believed were funny. The Tramp’s trademark baggy trousers, tight jacket, small hat and roomy shoes are something we can conjure in our imaginations without difficulty and the costume alone seems to sum up the Tramp’s nature entirely. Chaplin wanted to construct the character around a mass of contradictions. The Tramp’s clothes are tight and loose, he stumbles in and out of adversity, enjoying happy coincidence and rocky circumstance as he goes. There is no continuity to the Tramp’s life and he seems to be loved and hated in equal measure throughout his films. He is the everyman and he is the smallest cog of the crowd. We love the Tramp because, in him, we can all find a part of ourselves.

Mabel’s Strange Predicament saw the Tramp in his final incarnation, (although not in his first cinematic debut) bringing the bittersweet character to viewing attention for the first time. Released in 1914, the film follows well to do Mabel as she is run into by the Tramp figure, in increasingly bizarre situations. Whilst the film lacks the narrative development of later Chaplin works, it sets up the Tramp as a comic, anti-social figure. Everything that he does seems to spark chaos and it would be very easy for the audience to dislike the figure in the same way that the characters do. However, the increasing ridiculousness of the film’s events teamed with the Tramp’s lack of self-awareness means that it is nearly impossible to feel any sort of malevolence towards the character. Whilst the film features the Tramp as a comic figure, the heartstrings of audiences were already being tugged.

The Kid was Chaplin’s directorial debut and, unsurprisingly, centred on the Little Tramp figure. With a narrative much more complex than early cinematic appearances, The Kid follows a baby, abandoned on the street by his parents. Left in a car that is later robbed, the Tramp somehow gains responsibility of the child, eventually agreeing to rear him as his own. As the child grows, the two become partners in petty crime, breaking windows so that the Tramp can then repair them. The film follows the pair’s life together, filled with sufficient peril and heartbreak to hook its audience completely. The Kid shows the Tramp figure at his most lovable and in the shades of his personality, we fall in love with him again and again. The most alluring part of the Tramp is the fact that he is inherently imperfect. Against rigid social expectations, he makes it ok to slip up and go against the masses.

City Lights continues on a similar theme, dipping back into waters a little more slapstick. Following the Tramp’s tentative forays into first love, the film shows his attempts to woo and save a blind girl from economic ruin. Making inconsistent friends with a millionaire, seems things to start to go in the Tramp’s favour and when he is given $1.000, all seems to have come up roses. Sadly, it is not to be so. Robbers steal the money and although the tramp saves his girl, he ends up in prison. All is not lost, though. Before going to prison, the Tramp had saved the money and given it to the girl. A quintessentially happy ending ensues. Despite the neatness of the film, it never feels trite or overworked and that is primarily due to the presence of the Tramp. Adding a much needed comic touch, the Tramp carries the film as an emotive piece, not holding still long enough for it to migrate into one specific mood.

The Tramp left cinema in Modern Lights, all too soon. A study on the industrial and technological changes occurring in the world at the time, the film places the Tramp in a bafflingly complex production line, in which chaos inevitably ensues. Escaping from the factory, the Tramp meets a helpless girl and soon, the pair are struggling together to make a life in the big city. The Tramp never officially speaks as Chaplin had reservations about introducing him to the talkie era; however, there is a song in the film in which we hear the character singing a sort of gibberish. Perhaps, attached to the silence, the Tramp could be relevant to more people because he was a symbol for something, rather than being a real human. If he spoke, he would become ever more real and were that to happen, he would not be able to inhabit the dark space within all of us in which we all feel alone. When the Tramp was there, we all knew that, someday at least, it would all get a little better.