Like it or not, France has a massive hold over the way in which we think about cinema. From the Lumiere’s cinematic origins in the late 19th century all the way up to next month’s Cannes Film Festival, when we think or talk about cinema, we are tapping into a part of French history. Whilst we may associate French cinema with a very specific type of lifestyle, there is a huge, rich filmic archive in the country’s history. Early silent studies moved into narrative films which in turn moved to surrealism. We had detectives and femme fatales, we moved to dark social works through to terrible slapstick comedy. French cinema is an iceberg and when we think about it, we conjure up only the tip.

In truth, it’s impossible to think about “French Cinema” as a complete thing in itself; it is fluid, varied and moving. We can’t pigeonhole a thing which, by nature, is conflicting. Therefore, we won’t. Instead, it might be worth thinking about this cinematic behemoth in reference to its most loved and quoted era, the cinematic movement to which we all go when we conjure up an image of France on screen. The French New Wave was born from the minds of a group of film critics who believed that it should be the director, not the star, who was credited with the glory from a film. Taking their written arguments from the pages of Cahiers du Cinema, this group of experimental directors coined the phrase “camera stylo”, in which the relationship between director and camera was likened to that of an author and his/her pen.

Whilst there are many directors who contributed to the New Wave, changing what it meant to be a director during this era, the five originators are still the names that everyone remembers today. Although we all have our favourites, the combined works of the filmmakers are what really made the movement what it is.

Claude Chabrol

In 1958, Chabrol wrote, produced and directed a film called Le Beau Serge, a film which is often credited as being the first film of the French New Wave. The film centres in the relationship between two young men in a small French town. After having returned home to recuperate following a bout of TB, Francois reconnects with his friend Serge, who is worryingly depressed in his current life. The film was shot over just 9 weeks, utilising natural light and sound and unlike Hollywood films at the time, represented working class life as it was. The success of the film really made Chabrol the director he is remembered as today and whilst he soon ventured into territory much more Hitchcockian, it is his early work which defines, for many, who he was.

Jean Luc Godard

The man, the myth, the legend. Still making films today (with varying degrees of success), Godard is more often than not the first name that springs to mind when we think of the French New Wave. His film A Bout de Souffle (Breathless) is perhaps his most well known, taking place over the course of a few days in Paris. Godard was the first director to use jump cuts for non-narrative purpose and the scene in which Patricia and Michel drive through Paris is now one of the most quoted in cinematic studies. Whilst his typically French angle might not be to everyone’s tastes, Godard has more than made his mark as a stalwart of international cinema.

Jacques Rivette

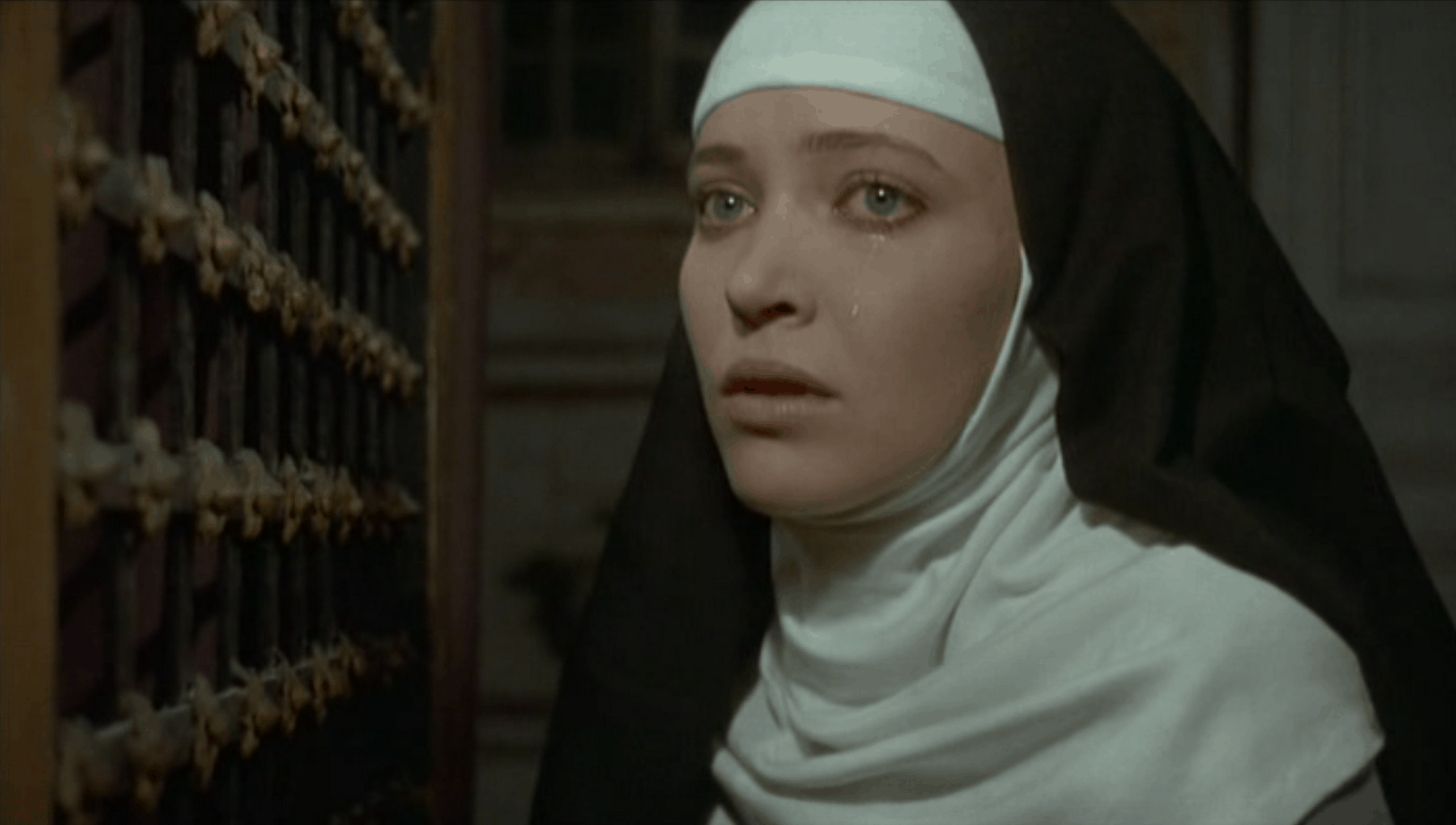

Out of the original 5, Rivette is best remembered as the director with intrigue and mystery; his films are punctuated by complex, unexpected turns and whilst they have been consistently critically approved, they have failed to find a lasting mainstream audience. Rivette was much slower whilst working than his contemporaries and whilst the other directors could pump out work after work, he studied his films with an eye decidedly more perfectionist. Of course, Rivette did manage to make a number of work with influence and it was his 1966 release La Religieuse that he made his first biggest success. But was it down to the plot or was it due to Anna Karina? Who knows, but one thing’s for sure; Rivette will always be remembered in cinematic history.

Eric Rohmer

One of the more commercially successful directors in the original group, Eric Rohmer was consistently obsessed with love and relationships in his films. Whilst the other directors tended to include long stretches of complex and philosophical discussion, Rohmer tended to champion a cinema more quiet and it’s no surprise that he was known for his astute and witty reflexions more than anything else. Rohmer is the New Wave director about which the least information is known and whilst his works were consistently intimate, there is very little sense of what he was like as a man within them. Although he is known for his preference for film series, it was his 1969 film Ma Nuit Chez Maude which really made his name. Rohmer endures as a master of cinema and looking back at his work, it’s really not hard to see why this is so.

Francois Truffaut

Equally as renowned as Godard in the film world, Truffaut has proved to be something of a major player in the film world. It is Truffaut’s semi-biographical film The 400 Blows for which he is truly remembered today. Depicting events (some fictionalised) of the director’s troubled upbringing, the film cemented Truffaut’s place on the cinematic stage and initiated the long term collaborative relationship that he would enjoy with actor Jean-Pierre Leaud. Out of all of the French New Wave directors, Truffaut enjoyed arguably the most success and even when things looked bad for the movement, he managed to maintain a certain degree of success.

Despite their move to a more intellectual type of cinema, all of the directors were openly influenced by American filmmakers and cinema. Whilst, however, we typically think of mainstream success and the Hollywood system, the New Wave directors proved that there is more to success than sheer numbers alone. Now, 60-odd years later, it is the New Wave directors who continue to last in the hearts of film lovers everywhere.